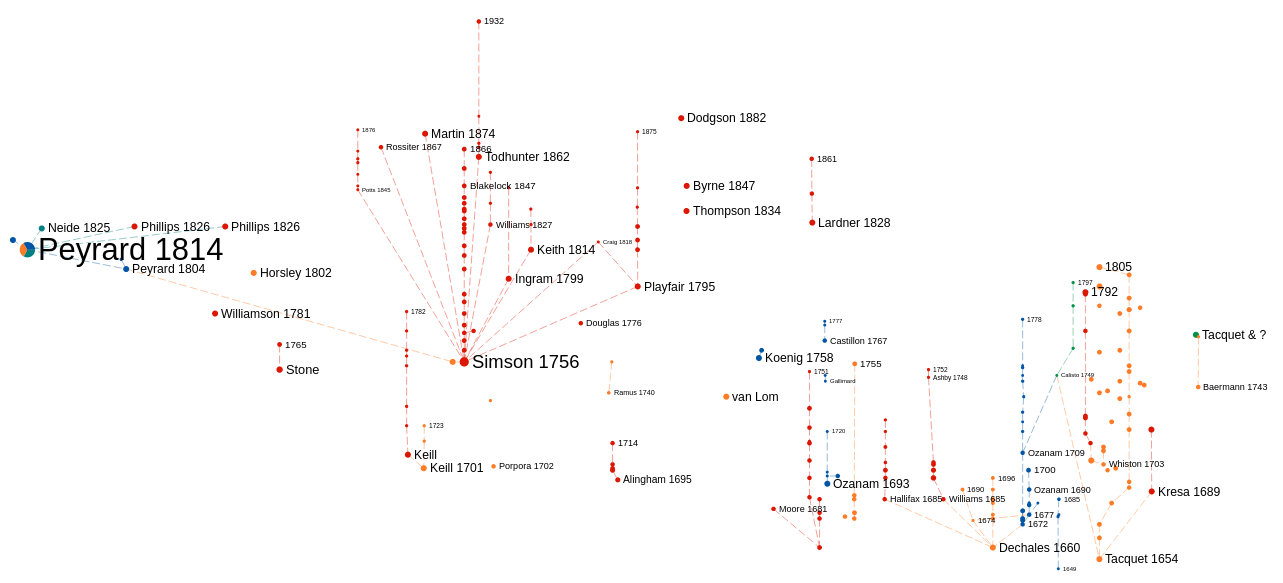

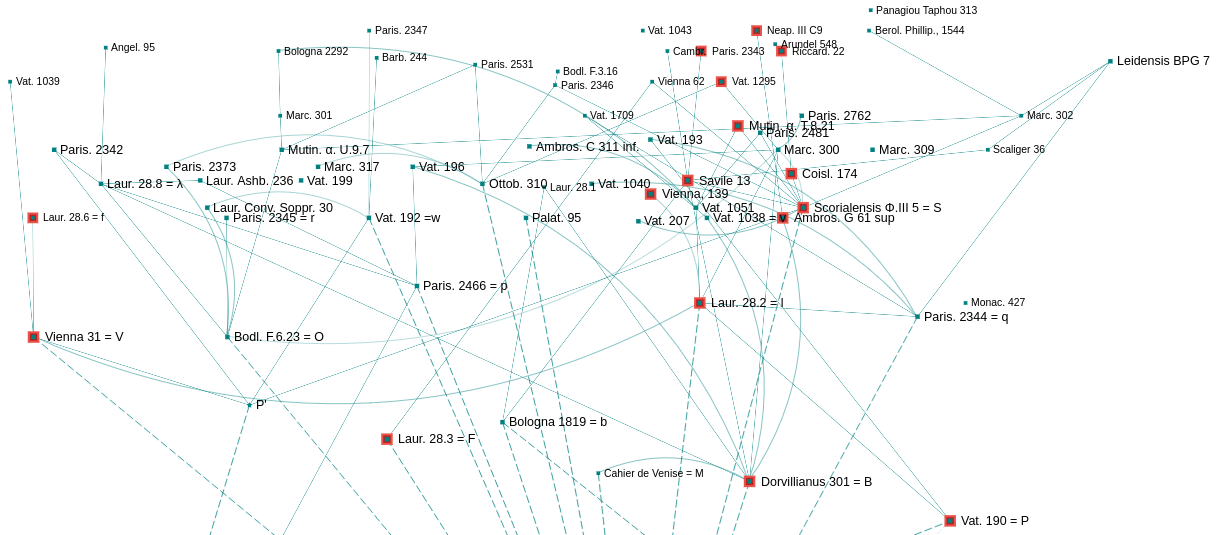

The nodes

Manuscripts and printed editions

The primary and main purpose of MÉδÉE is to facilitate access to digitized copies of different versions (manuscripts and printed editions) of Elements hosted on various sites. Reading and comparing them are ultimately the only means to truly understand, and potentially correct, the information provided about their sources and their often unique and complex relationships with them. The graph does not claim and cannot claim to replace the reading and study of the texts.

Access to digitized editions

The nodes include:

the main manuscripts (Greek, Arabic, Syriac, Armenian) of Euclid’s Elements;

the ancient Latin translations, followed by medieval Arabic, Latin, and Hebrew translations

the main printed editions;

the re-editions of the printed editions;

In order for a text (manuscript or printed) to be included in MÉδÉE, it must clearly demonstrate the intention to reproduce the Elements, in whole or in part. The treatise has undergone various editorial operations that could have affected the extent of this reproduction: amplification, commentary, epitome (e.g., omission of proofs), partial publication (sometimes limited to a single book), etc. Writings containing mere citations (so-called indirect tradition) are excluded, as are commentaries, even though they may sometimes transmit substantial citations useful for reconstructing the history of the text. This is the case, for example, with the commentary on the first Book by Proclus of Lycia (In Euclidem I), whose textual lemmas represent almost an entire booklet of results from said Book (principles + statements of Propositions). The number of such commentaries throughout the history of the Elements has been such that their inclusion would unduly inflate the graph.

The inventory of manuscripts and printed editions cannot claim to be complete.

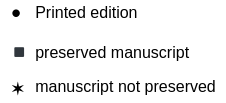

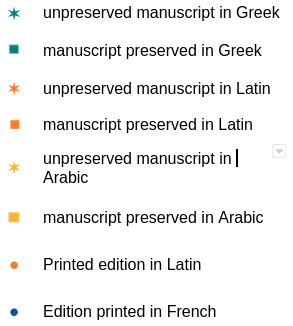

Three types of texts are distinguished in the graph:

The three types of nodes

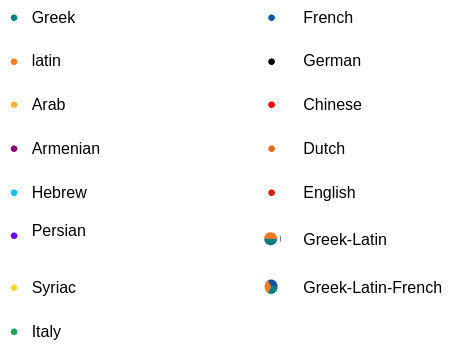

The language(s) of a text are indicated by the color of the node, which may combine multiple languages:

Color codes for the languages of the nodes

Examples:

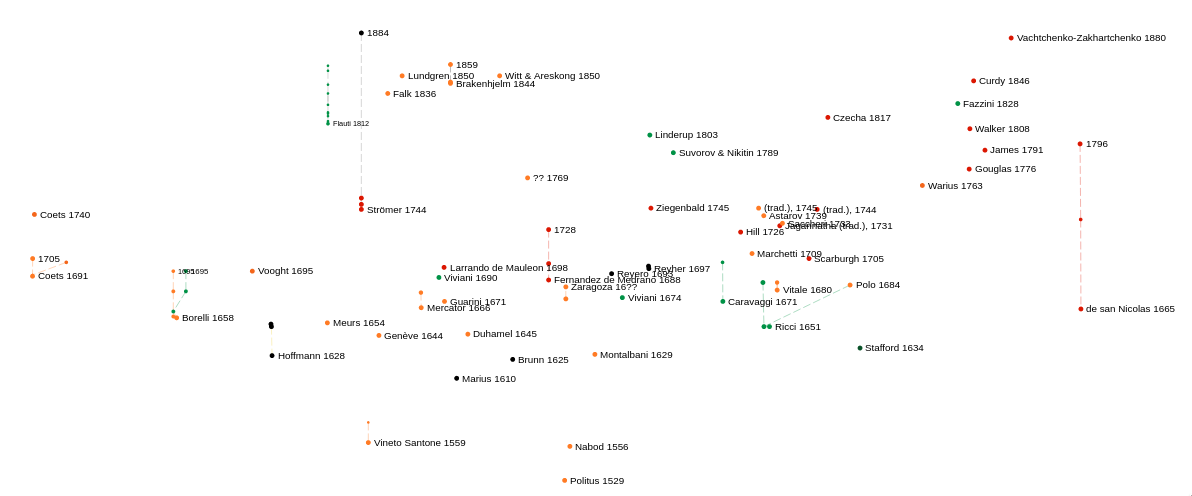

The distance between nodes, measured vertically, is proportional to the time separating the corresponding texts. Time is oriented from bottom to top. Horizontal distance has no particular significance.

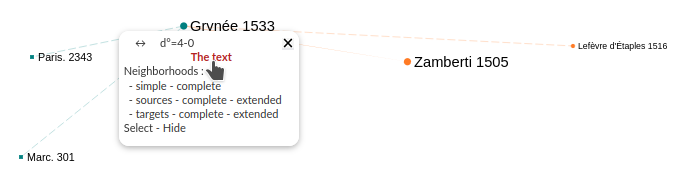

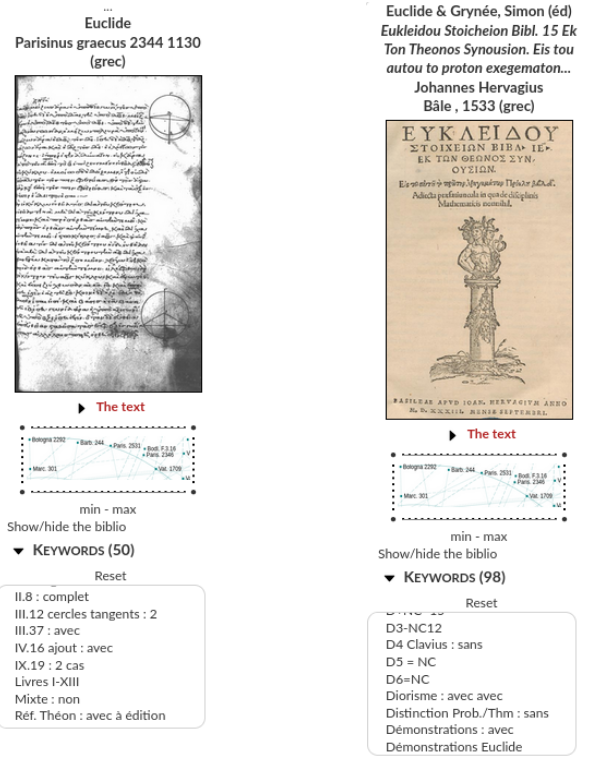

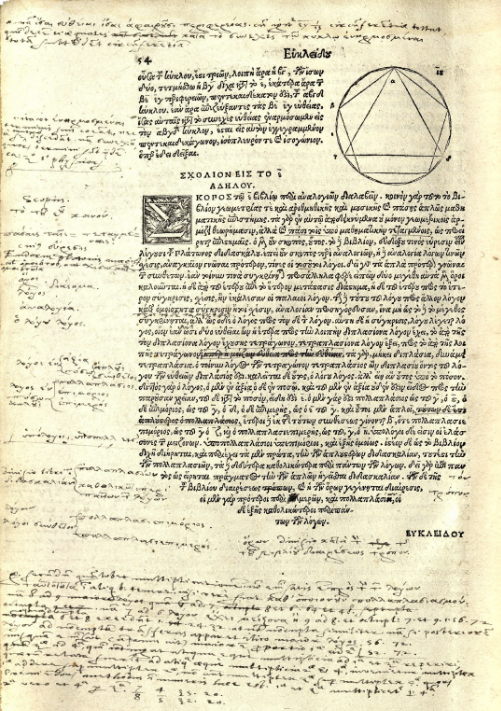

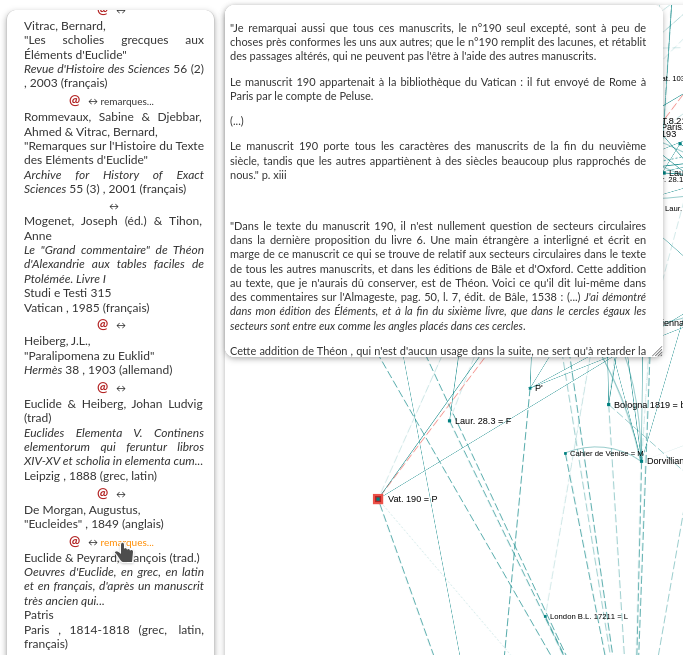

MÉδÉE provides for each node (left-hand box):

the codicological or bibliographical reference;

an image of a folio or title page;

the URLs of available online digital reproductions;

keywords.

Cartouches d’information sur des nœuds

Manuscripts

Manuscripts

The selected manuscripts illustrate the different languages of knowledge in which the text has been transmitted: Greek, Latin, Arabic, Persian, Syriac, Hebrew, Armenian, and even Italian, the first medium for vernacular translations in the 15th-16th centuries.

The completeness of their inventories in specialized literature varies greatly for both historical and historiographical reasons. Depending on the case, the extant witnesses can be numerous or unique. The value of the inventories listed in MÉδÉE should be specified in each case.

For the sake of readability, often only the most significant or chronologically close witnesses to an author’s version are included. The corresponding entries indicate where to find the lists of manuscripts, if they exist, if they are too numerous to be effectively displayed on the graph.

Whenever possible, a link to a digitized version of the manuscript has been provided. This has not always been possible, as some libraries do not facilitate access to their digitized manuscripts.

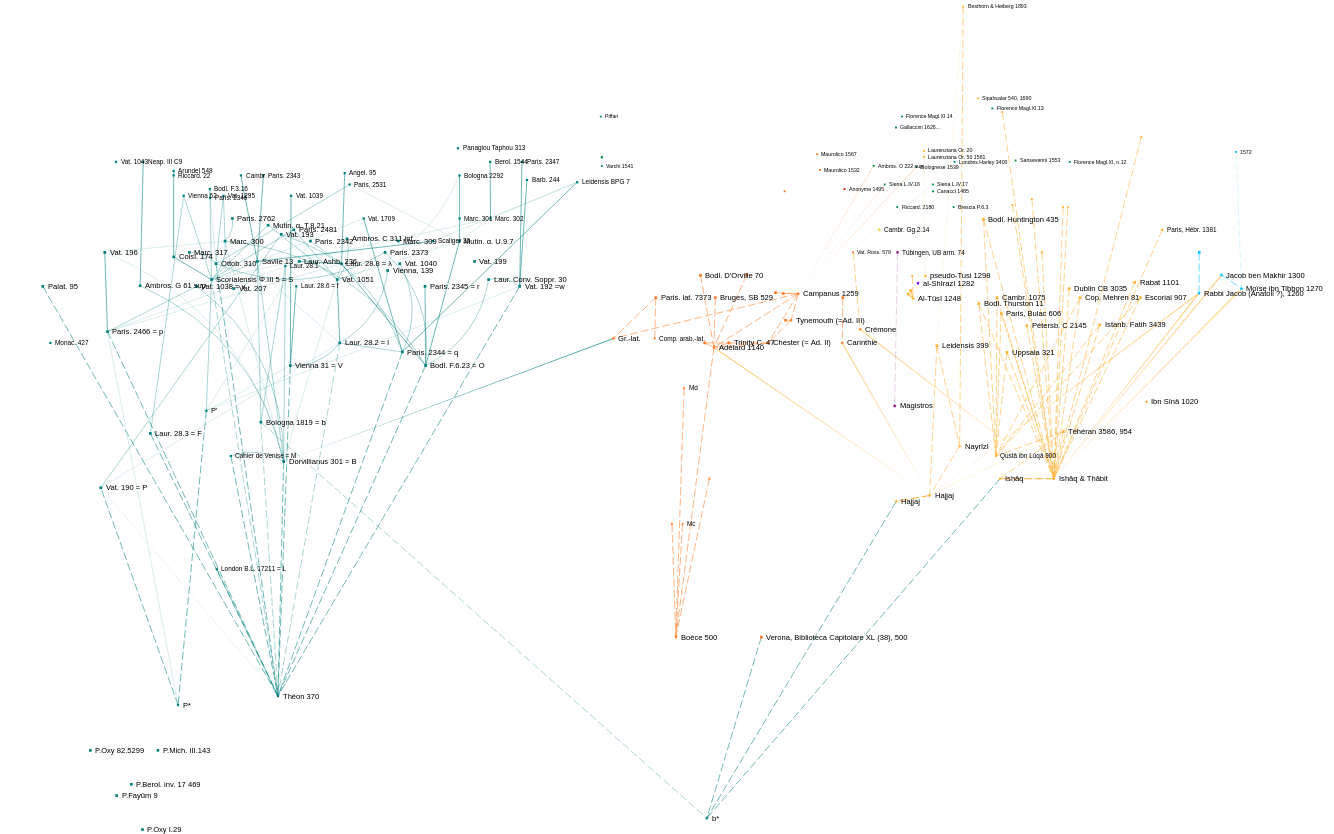

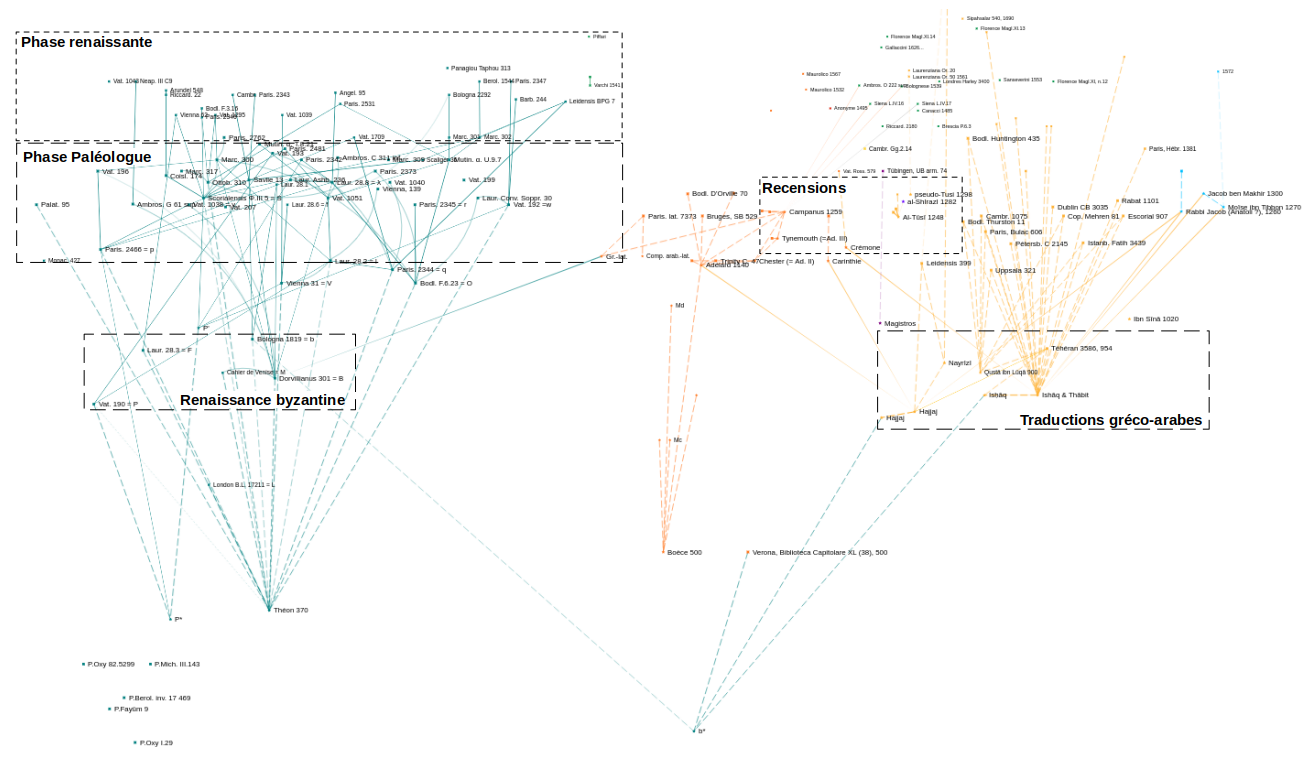

Periodization of the history of manuscripts

Besides the linguistic aspect, MÉδÉE also displays the significant periods in the history of the text prior to the invention of printing:

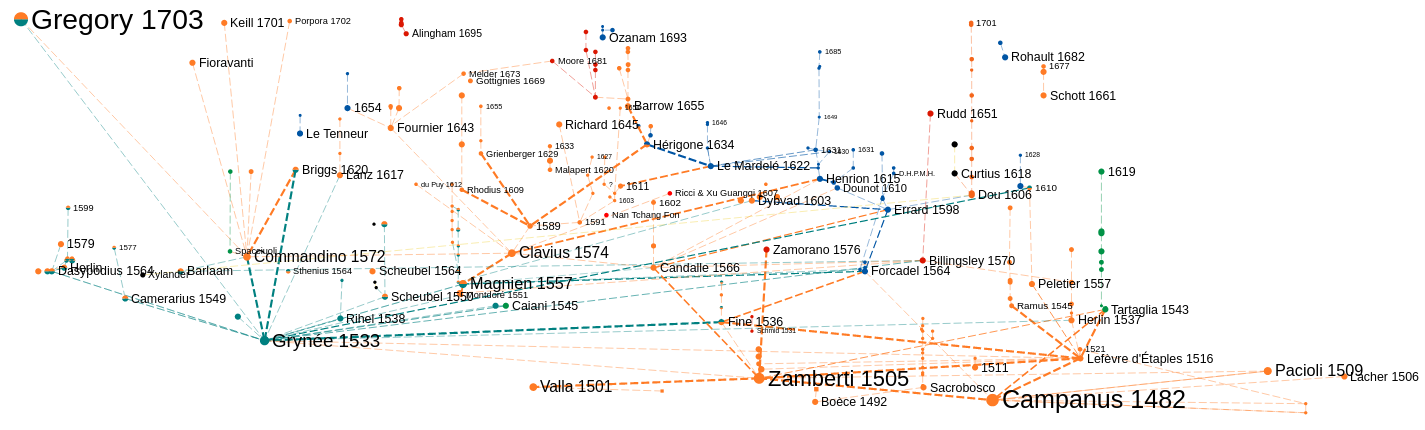

There, we can distinguish a first group, ‘Byzantine Renaissance’ (9th-10th centuries), corresponding to the transliteration of the text (transition from uppercase to lowercase writing), which is responsible for our oldest complete Greek manuscripts.

On the right, during the same period, the group of Greco-Arabic translations appears, which is not connected to the Greek nodes. These translations are highly significant for the history of the text, as they are based on Greek manuscripts that are now lost and had a considerably different structure compared to the preserved Greek manuscripts.

After a sparse period, the beginning of a new group called the ‘Palaeologan Phase’ becomes distinguishable. From 1260 to 1453, there was indeed a thriving scholarly activity in Constantinople focused on ancient Greek mathematical texts, including Euclid’s Elements (as well as Nicomachus of Gerasa’s Introduction to Arithmetic and Ptolemy’s Almagest).

After the period of translations (9th-12th centuries) and the gradual reappropriation of the text, we can distinguish in the 13th and 14th centuries, both in Latin and Arabic, much more personalized treatments of the treatise (‘recensions’), which nevertheless maintain its structure. Among the most famous are those by Campanus of Novara and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi.

From the late 14th century onward, the Western world experiences a renewed interest in ancient Latin and Greek texts. The fall of Constantinople amplifies this phenomenon, and a ‘recovery of Greek’ is organized, justifying the fact that most preserved Greek manuscripts are now found in European libraries. A new period of copying (‘Renaissance Phase’) emerges, often based on models produced during the previous phase (‘Palaeologan’), without interruption but with a relocation, first in Italy and specifically in Venice, and then throughout Europe.

All these manuscripts play a crucial role in the recent phase of critical editions of different versions, which are still ongoing, and whose completion can be expected, especially regarding the Arabic and Hebrew domains.

The label of nodes associated with ‘eliminable’ manuscripts, which are copies of preserved exemplars and therefore irrelevant for critical edition, is displayed in a smaller font size. The same convention has been applied to fragments (L and M), as well as to manuscripts containing only the Additional Books (XIV and XV).

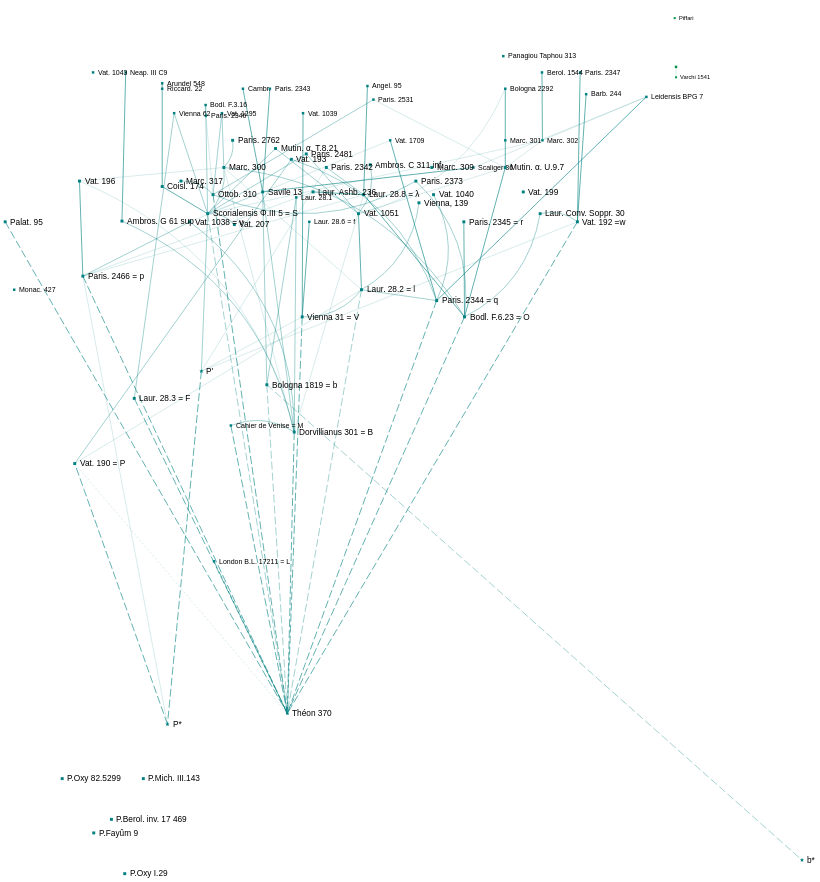

The Greek Manuscripts

The Greek Manuscripts

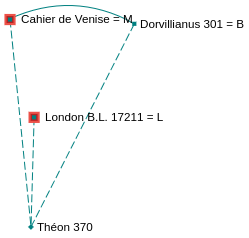

The case of Greek manuscripts is particular due to the critical edition project of one of the authors. Currently, only codices dating before the end of the 16th century and of a certain extent are recorded, amounting to about sixty witnesses out of a possible total of around 130. These include those that are relevant or potentially relevant to the constitution of the text. However, it should be noted that manuscript copying did not cease with the advent of printing: there are about twenty copies of the Elements made after 1600, indicating the dissemination of the treatise but without significance for the textual history. These are omitted in MÉδÉE, as well as the result sheets (principles and statements only; 13 are preserved) and fragments, with the exception of two [London B.L. 17211 (= L), Cahier de Venise (= M)] due to their great antiquity:

Un inventaire de tous les manuscrits grecs recensés des Éléments est proposé dans l’Annexe 1 de Vitrac, Préalables …, 2023. Il inclutquelques exemplaires portant seulement des scholies au texte des Éléments (annotations marginales éventuellement recueillies en collections séparées) qui ne se trouvent pas non plus dans MÉδÉE, conformément à la définition d’un « texte euclidien (manuscrit ou imprimé ») donnée plus haut. Celle-ci admet toutefois une exception : MÉδÉE enregistre trois exemplaires (Monac. gr. 427, Vat. gr. 1039, Cambr. UL 1463) qui portent uniquement les Livres additionnels XIV-XV, voire le seul Livre XIV ; à strictement parler, ce ne sont pas non plus des manuscrits d’Euclide, mais il a semblé nécessaire de les inclure.

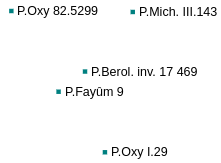

Before Euclid’s text was transmitted in books with pages, it circulated in the form of papyrus scrolls. Testimonies from this early period of Greek literature are very rare for mathematical works but significant, especially due to their antiquity. The oldest evidence regarding Euclid is the P. Herc. 1061 (2nd-1st centuries BCE), which quotes excerpts from several propositions of the Elements. However, it was not considered as it is an excerpt from Démétrios Lacon’s On Geometry. Therefore, it is the oldest witness of the indirect tradition, not an actual Euclidean copy as defined above. On the other hand, five papyrus fragments dating from the 1st-3rd centuries are included in MÉδÉE. They transmit tiny portions of the text, including a fragment of a bundle of results, P.Oxy 82.5299.

MÉδÉE favors existing copies and, unlike some stemmata, does not multiply the disappeared witnesses (✶) required by philological constraints. In the Greek domain, only the following have been introduced:

— the original copy of the re-edition by Theon of Alexandria (ca. 350-370);

— two independent models (non-Theonian) that need to be postulated because the scribe of the Vaticanus græcus 190 used such a model (P*) and because certain manuscripts (called mixed) also used a non-Theonian copy, but distinct (P’), and

— an independent model of Theon of Alexandria’s re-edition and the non-Theonian text of the family (P, P*, P’) that needs to be postulated to account for the structural similarities between the Arabic and Arabo-Latin versions on one hand, and the particular recension of Propositions XI.36-XII.17 of the Bologna codex (b) on the other. Indications show that the Latin palimpsest of Verona (a translation by Boethius?) also bears some relationship with this version, which is the oldest stratum of the text that we have (partially) access to. This model could hypothetically be related to the time of Heron of Alexandria, the oldest commentator of the Elements known to us.

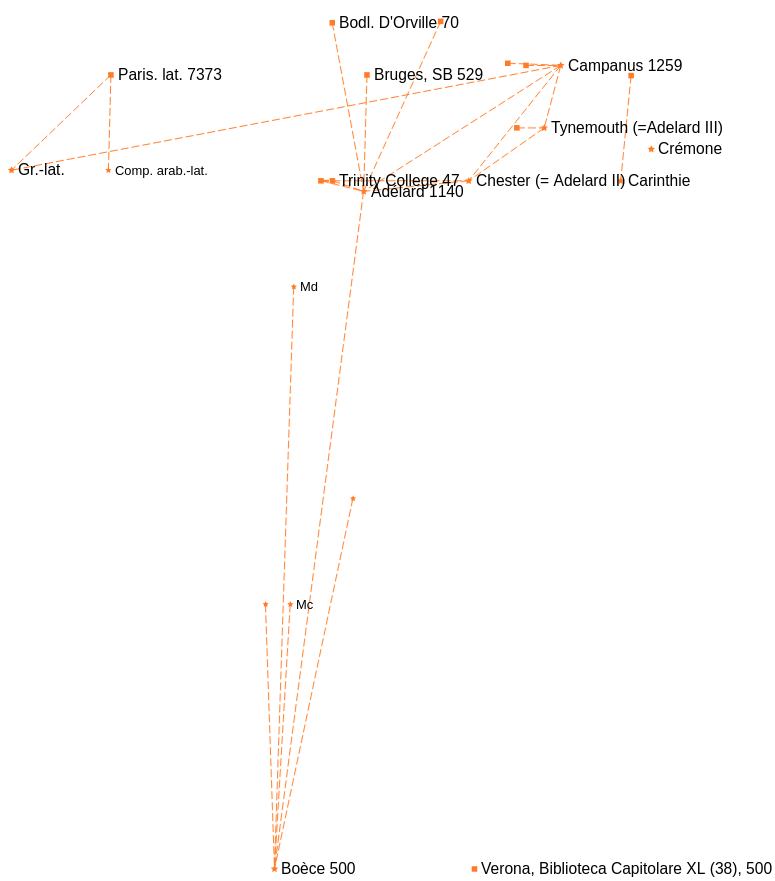

The Latin manuscripts

The Latin manuscripts

The recorded Latin manuscripts correspond to: ancient Greco-Latin translations — notably the one attributed to Boethius —, medieval translations (the anonymous version made in southern Italy around 1160), and especially the Arabo-Latin versions that saw a first recovery of the complete text in Spain in the first half of the 12th century. Only a few witnesses are mentioned, particularly for the versions where they are very numerous (Robert of Chester, Campanus of Novara), and the originals of the different versions (now lost) are indicated as such ( ). There are many other medieval Latin recensions, often anonymous, which have not been included here. Folkerts 1989/2006 provides the most comprehensive census of these versions and the manuscripts that contain them. For the lost originals, the oldest preserved manuscript is shown on the graph.

). There are many other medieval Latin recensions, often anonymous, which have not been included here. Folkerts 1989/2006 provides the most comprehensive census of these versions and the manuscripts that contain them. For the lost originals, the oldest preserved manuscript is shown on the graph.

Arabic manuscripts

Arabic manuscripts

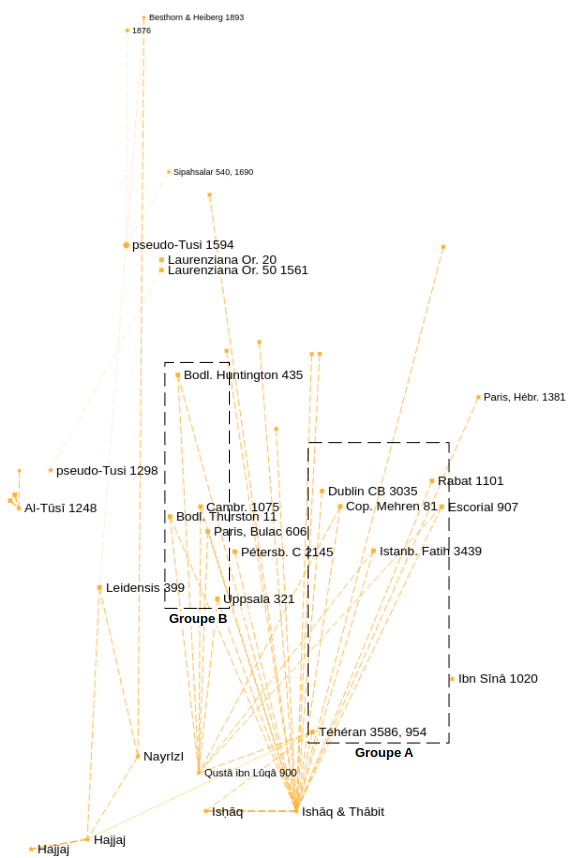

In the Arabic domain, MÉδÉE lists the identified copies to date of the Greco-Arabic version known as Ishâq-Thâbit (translator = Ishâq ibn Hunayn; reviser Thâbit ibn Qurra); some of them transmit fragments attributed to the other translator, al-Hajjâj.

Gregg de Young, editor of the arithmetic books of the so-called Ishâq-Thâbit version, has proposed a distribution of manuscripts into subgroups, notably two families called A and B, which are visible in the spatial distribution in MÉδÉE.

group A (to the right of the Ishâq-Thâbit cone): Tehran 3586, Istanbul 3439, Copenhagen 81, Dublin CB 3035, Escorial 907, Rabat 1101, etc.), in which a subgroup of witnesses called ‘andalous’ emerges (Escorial 907, Rabat 1101, Rabat 53, Paris. Hébr. 1381);

group B (to the left: Uppsala 321, Thurston 11, Cambridge 1075, Huntington 435).

Some witnesses, such as Pétersbourg C 2145, do not fit well into this outline of classifications. Its scope extends beyond the arithmetic books but probably does not apply to the entire treatise. The text of the stereometric books appears exceptionally homogeneous. These different divisions may be explained by the role that certain sub-archetypes may have played or by the interaction with the translation(s) of al-Hajjâj.

For the recensions in the Arabic language (Ibn Sina, an-Nayrîzî, and especially Nasîr ad-Dîn at-Tûsî), MÉδÉE only mentions their existence. The same convention as in Latin (here  ) is applied. The selection of recensions here is even more selective than in Latin (see the abundant but provisional list given in [Sezgin V, 1974], pp. 104-115).

) is applied. The selection of recensions here is even more selective than in Latin (see the abundant but provisional list given in [Sezgin V, 1974], pp. 104-115).

The only witness of a translation into Syriac, of which a fragment of Book I (Cambr. Gg. 2.14) remains, and a ‘complete’ copy of the fragments (I.Df.-Prop. I.3) of the Armenian translation (Tübingen UB arm. 74) are also mentioned.

For the Arabo-Hebrew translations, the same convention as for the Arabic recensions has been applied without detailing the manuscripts that carry them. The most complete inventory to date lists 31 copies; it can be found in Lévy’s article (1997), to be supplemented with the note 1 of his 2005 study.

Printed editions

Printed editions

The nodes for printed editions no longer represent unique documents, but different ‘editions’, which are actually sets of distinct documents based on the date, printer, and place of printing.

Copies of the same edition that are supposed to be “identical” are not always so. Various corrections can be made during the same print run. This phenomenon is not unique to incunabula, as Volume 2 (1816) of the trilingual edition by Peyrard experienced this kind of adventure (see Vitrac 2023, “Préalables…”, Section 3, §VIII).

Copies are often annotated and therefore become unique, as all manuscripts are. This is particularly the case with the copy of the Grynée edition, abundantly annotated by Savile and undoubtedly used for the Gregory 1703 edition (Vitrac 2023, “Préalables …”, Section 1, §IIb).

Exemplaire annoté de Caiani 1545

For this reason, multiple URLs are given whenever possible for the same node, referring to actually different and often annotated copies.

The copy used for studying the relationships between editions and the allocation of keywords is the one indicated by the first URL, disregarding its manuscript annotations.

Thus, a node represents a set of documents distinct from those of another node, but they can also differ among themselves, represented by the copy associated with the first given URL.

When it does not lead to confusion, we will commonly abuse the terminology by confusing the node, the edition it represents, and the text that represents this edition.

The recorded printed editions include most of the editions listed in the catalogspublished before or during this work, and as much as possible, all those available online. The catalogs that list a given edition are listed in the publications that cite it (see below).The URLs provide direct access to nearly 400 digitized editions and reprints available online, facilitating access to these editions, their consultation, and the verification of the proposed analyses. The inventory of digitized editions often allows for complementing and sometimes correcting the data from these catalogs. Representing their reprints in space allows for visualizing the longevity of the editions.

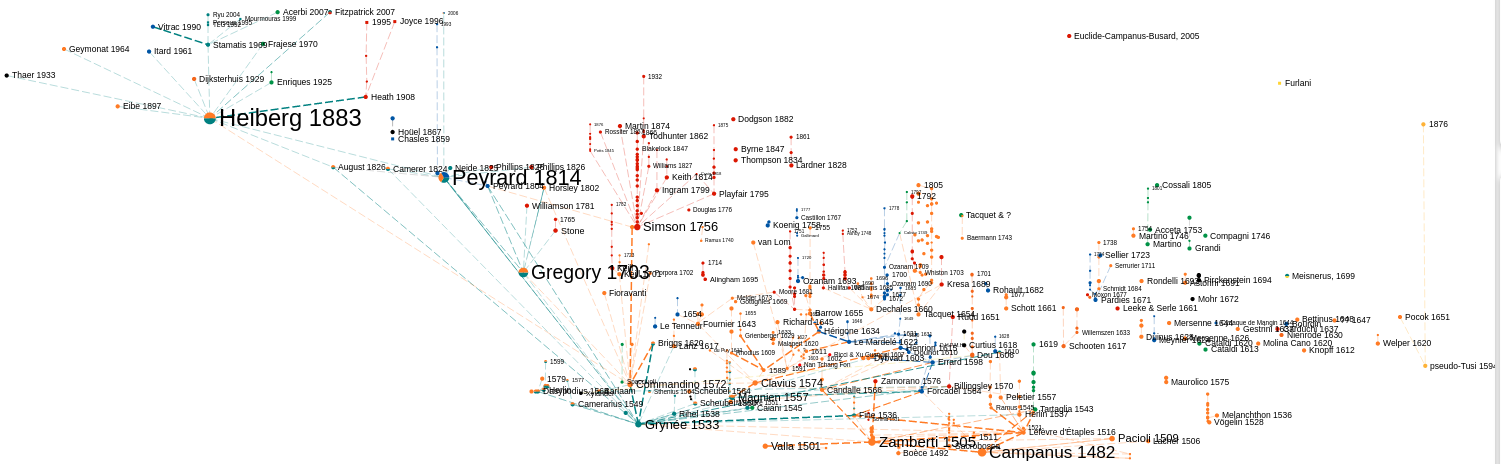

The nature and level of analysis of printed editions vary greatly. Four regions of the graph and three historical periods can be distinguished:

printed editions before 1703

printed editions between 1703 and 1883

printed editions after 1883

purgatory (especially after 1600)

Printed editions before 1703

The studied printed editions

The printed editions published from Campanus 1482 to Gregory 1703 are the ones we have analyzed the most due to the study we conducted on the use of Greek sources in the early printed editions. Most of these editions (for those that are not in the purgatory) have been studied to justify the links indicated on the graph, extensively for Book I, and occasionally for others, particularly by exploiting the structural variables derived from the study of manuscripts (of which only a very small part is found in the :ref:`keywords <documentation_motsclefs>).

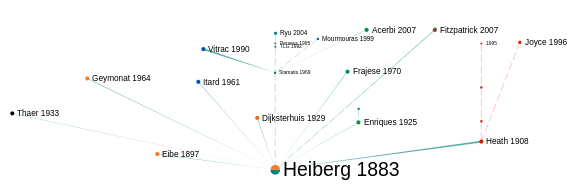

Printed editions after 1883

Printed editions after Heiberg (1883-2007)

Publications subsequent to Heiberg’s critical edition of the text can be divided into three categories:

— Those that reproduce it (re-editions, digital versions);

— Translations that refer to Heiberg’s edition. For these editions, the links often only reiterate the indications given by their authors, which we generally consider reliable.

— Critical editions, complete or partial, of versions written in other languages (Arabic, Latin, Syriac, Hebrew).

The Arabic, Latin, Syriac, and Hebrew Critical Editions (1893-2021)

Printed editions published between 1703 and 1883

Printed editions between 1703 and 1883

The period between Gregory’s 1703 edition and Heiberg’s 1883 edition primarily includes Peyrard’s editions, especially the 1814 edition made following the identification of the peculiarities of the manuscript Vat. gr.190, Camerer’s Greco-Latin edition of 1824, and the Greek edition of August 1826-1828. It also includes numerous editions, mainly in English, used for teaching and adapted for this purpose.

We have added limited information about these editions, but the proposed census is, to our knowledge, the most comprehensive for the considered period.

The purgatory

The purgatory

In the right part of the graph, there are dispersed editions that have not been studied and contain limited information. For these nodes, the graph is little more than a catalog, although some have a URL to access the edition or a reference to a related publication. We are interested in any information about these editions and their sources.

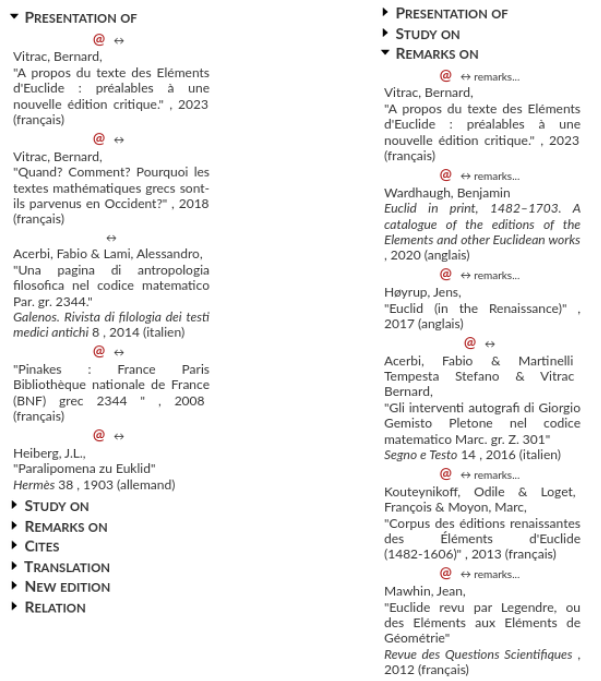

Secondary literature on the nodes

MÉδÉE provides a selection of secondary sources related to each node and a link to them when they are available online.

These secondary sources are classified into several non-exclusive types:

Text presentation

Text study

Contains remarks on the text

Cites the text

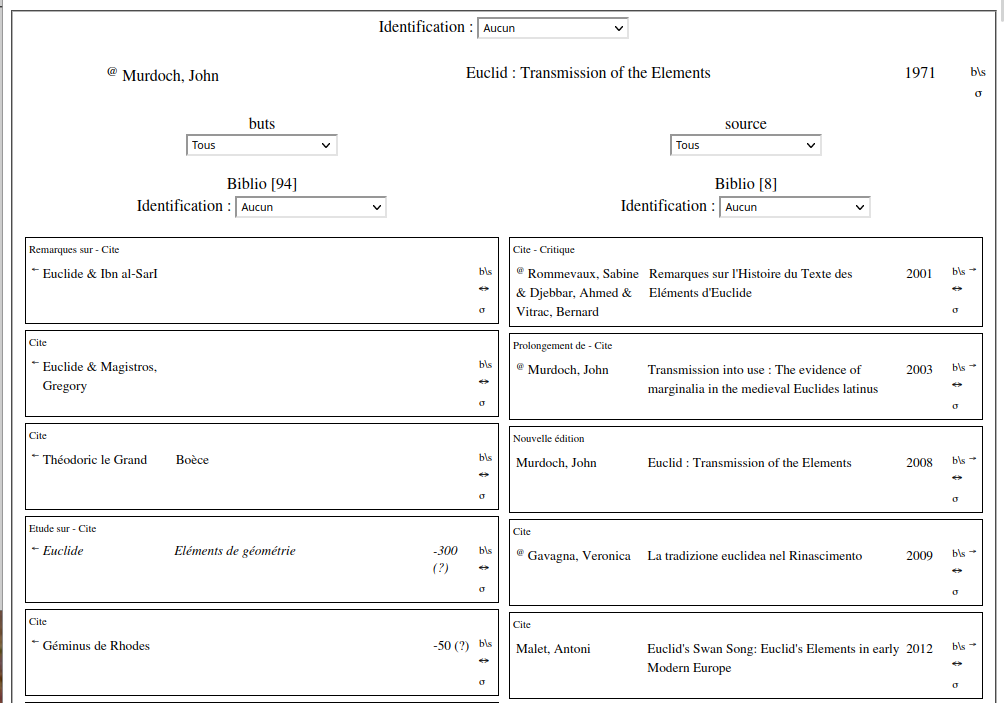

Bibliographies typed from two nodes

For each of the preserved Greek manuscripts, the presentation given in the Pinakes database hosted on the site of the I.R.H.T. is easily accessible from each node (in Présentation de) by clicking on the @:

These Pinakes presentations also provide useful and constantly updated bibliographical information. The description of the content is sometimes insufficient, especially for the three copies mentioned earlier that transmit the Additional Books (Monac. gr. 427, Vat. gr. 1039, Cambr. UL 1463).

Some remarks from a secondary source on a manuscript or printed edition are directly accessible from the corresponding graph node.

Remarks by Peyrard 1814 on Vat. gr. 190:

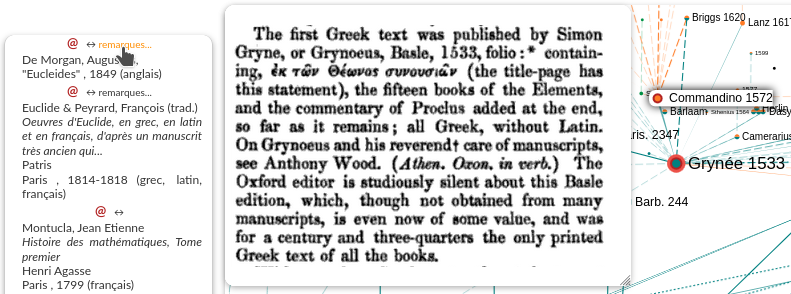

Remarks by De Morgan 1849 on the Grynée edition:

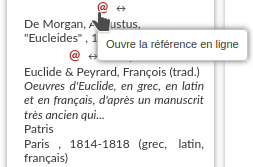

These remarks remain associated with the publication to which they belong and can be referred to when it is available online (@).

Access to the secondary source

The publications associated with the nodes are neither the result of automatic harvesting nor a selection of recommended publications.

The different types (‘text presentation’, ‘text study’, ‘remarks on’, ‘critique’, ‘cites’, etc.) indicate the nature and extent of the considerations devoted to a manuscript or printed work. They make it possible to distinguish publications that include a presentation of the text, those that provide a study of it, those that make remarks about it, and those that only cite it. Catalogs or bibliographies that do not make these distinctions are often not very useful in practice.

The references provided allow us to trace the evolution of interest in Euclid’s Elements. This includes observing the dissemination of certain assertions about their sources, often repeated independently of their validity.

For each publication, a double arrow (↔) allows you to display a list, more or less extensive, of publications that it cites, on which it makes remarks, etc., as well as those that cite it, make remarks about it, or possibly criticize it. These pieces of information provide incomplete but objective contextual elements about these references.

References cited and referencing a publication

Refer to the Documentation for more details.

Information about the nodes is also provided in the notices.

Keywords

Keywords, in varying numbers, are assigned to most nodes. See their complete list with their definition and the extent of their attribution. These keywords provide additional varied information about manuscripts and prints, including the main relevant differences for comparison. Coupled with the search and filtering features of the graph, they also allow the exploration of their filiations, which can then be controlled and supplemented by referring to the texts themselves.

Manuscrits grecs avec la scholie au Livre V et D5 = D

The attribution of keywords also depends on the region of the graph to which the nodes belong.

For the sake of readability, re-editions generally do not have keywords since they are the same as the original edition.

Description and dependencies

Keywords serve two functions: they are used for text description and the study of their dependencies. Some keywords contribute to both, some to only one, and for the same keyword, this can vary depending on the period considered.

For example, the number and distribution of Requests and Common Notions are always relevant elements for text description. However, they are less relevant for the study of their dependencies, both for manuscripts and prints, but for opposite reasons. The number and distribution of Requests and Common Notions vary very little in the preserved Greek manuscripts:

a principle is sometimes considered a Request (the last one, No. 6 when numbered), sometimes as a Common Notion, and

an additional Common Notion does not exist in all witnesses.

Except for these two, there is only one significant exception: in one copy (the Marc. gr. Z 301), Requests 4 and 5 were deliberately moved and transformed into Common Notions. This transformation will be found in the printed editio princeps of Grynée (and in the Greek manuscripts copied from it), but no other earlier copy.

On the contrary, authors of printed editions do not hesitate to modify these Common Demands and Notions, to introduce new ones, for mathematical reasons independent of the textual characteristics of their source. Thus, for example, the distribution of principles in the editions of Rhodius 1608, Dounot 1610, and Grienberger 1629 differs from that of their source, and therefore does not provide us with information about it.

More generally, aspects that have their own mathematical interest can be modified concomitantly and independently by different authors. They are therefore relevant for describing their edition but are less relevant for the study of filiations.

Aspects useful for the study of dependencies necessarily also contribute to the description of texts, but their relevance in this regard is often lower, especially because they may not have mathematical interest.

Extended and punctual keywords

The aspects recorded by keywords can be of two types: extended or punctual.

Extended aspects and keywords

The extended aspects (existence or absence of proofs, multiple numbering, distinction between problems and theorems, etc.), including the language (Greek, Arabic, Latin, etc.), are relevant because of their extension and are generally easy to determine for that reason. However, the precise determination as well as the exact representation of their extension is a very difficult problem. Reading the text is the only way for each person to form an idea of its extension, and it determines the extent of knowledge that each person has about it. But it is then very difficult even to retain the memory of this extension, let alone transmit it. The assignment of an extended keyword therefore only attests to the extended nature of the aspect under consideration, but without indicating its extension. This extension can only be determined by each person, for themselves, through the examination of the texts they have access to.

Punctual aspects and keywords

This problem of extension does not arise for keywords related to punctual aspects (number of Common Demands or Notions, existence or absence of the definition of complements, of the porism at I.15, cases treated in a proof, etc.), which are localized and have a reduced and predetermined extension a priori in such a way that their assignment and control escape extension problems.

The identification of certain aspects, not to be confused with their assignment or control, however, proceeds from an extensive knowledge of the texts, and even doubly extensive. An extensive knowledge of at least one text, and often two, is necessary to identify what is first and foremost a difference, unless one thinks it can be discovered by chance. An extensive knowledge of the corpus is then necessary to appreciate its relevance.

The punctual differences between two texts are countless and therefore easy to identify. However, the relevant and efficient differences for filiation studies are rare and much harder to identify. These are the differences that require a doubly extensive knowledge of the corpus. It concerns primarily observed differences between two texts, reformulated to define keywords whose attribution can be determined through the localized and circumscribed, i.e., punctual, examination of a single text. When we have these formulations, it becomes possible to disregard their elaboration and, in particular, the doubly extensive knowledge required to assess their relevance after their identification.

The punctual aspects, once identified, can be objectively attributed to each node and easily controlled by everyone due to their punctual nature. On the other hand, they provide potentially relevant but punctual indications about filiations (see also:ref:Keywords and links <motsclefs_et_liens>). They benefit from the doubly extensive knowledge required for their identification, allowing for a punctually reduced but extensive transmission throughout the corpus.