The links

Introduction

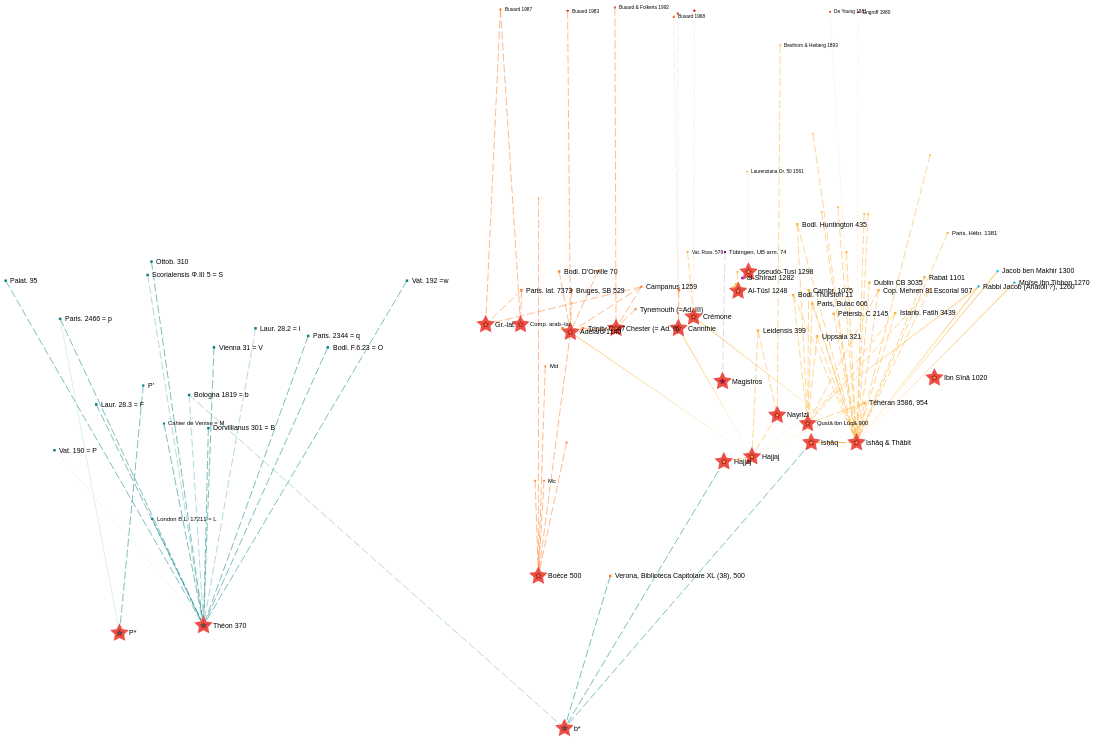

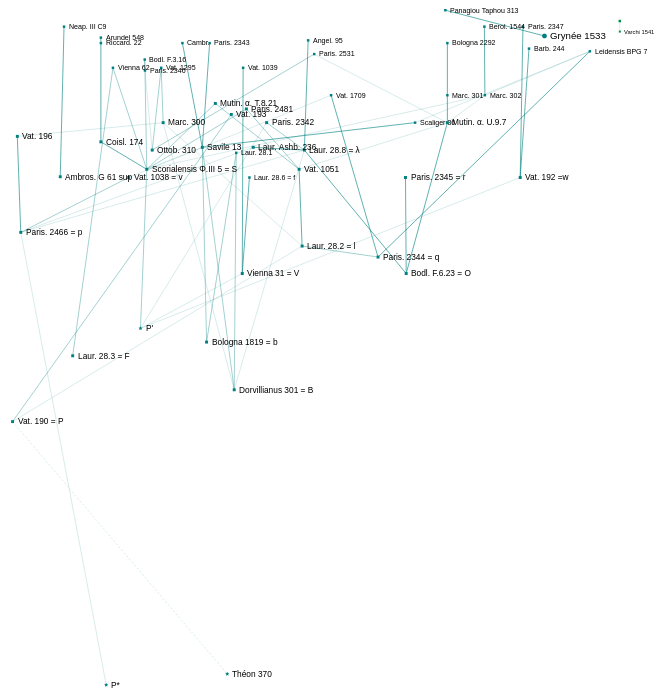

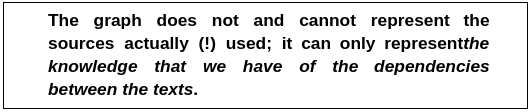

In addition to surveying the different versions of Euclid’s Elements, considering both manuscripts and printed editions, as well as related works, MÉδÉE enables the survey of their relations, including the publications related to them. The relations between texts are thus treated the same way as the texts themselves.

But before the Renaissance, no manuscript of Euclid’s Elements contains specific indications about its model. For printed editions, such indications are rare and, at least until Peyrard’s edition in 1814, unreliable. The editions mentioned in their commentaries are not necessarily the ones used to establish their main text (definitions, requests, common notions, statements of propositions, and their demonstrations) to which, unless otherwise indicated, the analyses are limited for printed editions. Therefore, the links primarily represent the result of an analysis of the differences between the texts, not these indications.

The identification of a text’s sources and the characterization of its relation to them can often only be partial, incomplete, and, at least in that respect, provisional. Reading and comparing texts and the studies dedicated to them are ultimately the only means that each person has to understand the nature of a text’s relation to another. For this reason, MÉδÉE strives to facilitate access to these texts and the studies related to their relations through the links that represent them.

The basis of the represented links varies depending on the region of the graph for both historical and historiographical reasons. The relations between Greek manuscripts and some of the early printed editions have been analyzed separately by the two authors. The links in these two regions should be distinguished from those in the others for this reason.

The purpose of this section is to specify the meaning of these links and the relations they represent according to the different regions of the graph.

The source and purpose of a link

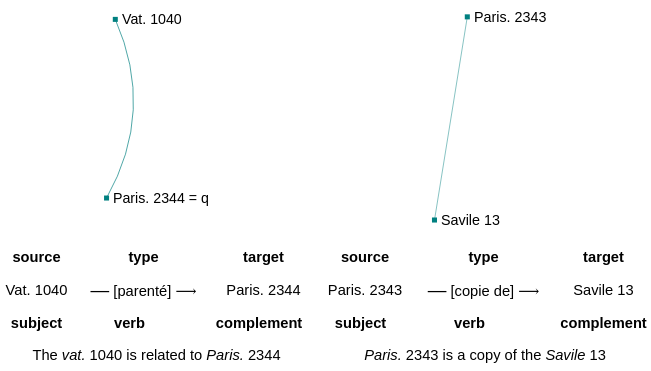

All links in the graph are oriented. They have a source and a target. The examples below indicate the conventions adopted in the graph.

The source of a link should not be confused with the source of a text.

The verticality of a link generally indicates the fidelity of a text to its model: a vertical link between two manuscripts indicates that one manuscript is copied from another. A vertical link between two printed editions indicates a reprint without significant identified changes between their main text.

Readability sometimes requires deviating from this rule. For example, translations in different languages and potentially numerous reprints of the same edition cannot all be placed vertically without overlapping. Some of them must be shifted.

Two nodes can also have multiple types of links between them (e.g., “nouvelle édition” and “traduction” for bilingual editions). It was decided to adopt a common form (straight line with short dashes) to avoid overloading the graph, knowing that the color of the nodes allows differentiation between new editions and translations: when the two nodes have the same color, the link is of type “nouvelle édition”, and otherwise it is of type “traduction”.

For Greek manuscripts, the thickness of the links distinguishes copies on almost complete portions of the text (thickness of 1), important portions (0.5), and lesser portions (0.1).

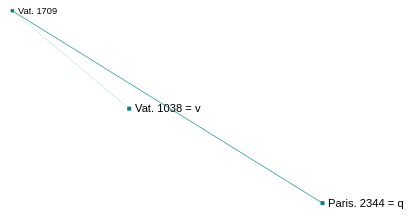

Thus, Vat. gr. 1709 is a copy of Paris. gr. 2344 on Books I-VIII.25 + IX.15-XIII (thickness of 1), and a copy of Vat. gr. 1038 on portions VIII.25-IX.14 + XIV (thickness of 0.1).

Opposition of links with thicknesses 1 and 0.1.

Relationships are all represented by links with a thickness of 0.5.

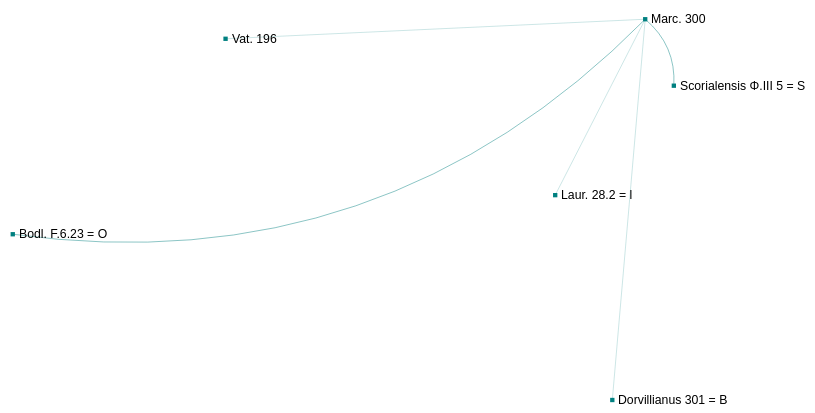

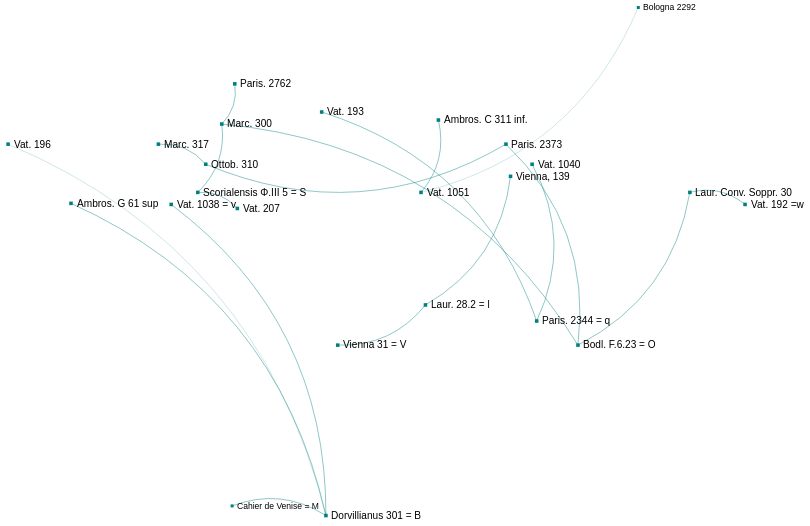

For example, Marc. gr. Z 300 has parentage links with O and S (thickness of 0.5) and is a copy of Vat. gr. 196 on the portion X.86-XII (thickness of 0.1), of Laur. 28.2 on Book XIII (thickness of 0.1), and of Dorvillianus 301 on X.18-87 (thickness of 0.1).

Opposition of links with thicknesses 0.5 and 0.1.

Types of links

Manuscripts and printed editions of Euclid’s Elements were necessarily created from one or more manuscripts or printed editions of Euclid’s Elements. It is these relationships that MÉδÉE seeks to determine and represent through links.

A link represents only the existence of such a relationship between the texts associated with each of its ends. The default type of this link is arbitrarily called ‘nouvelle édition’. Literally taken, this designation is inappropriate for manuscripts and indicates nothing more than the existence of this relationship.

A manuscript cannot a priori be better characterized in terms of how it was copied or translated than by referring to the manuscript from which it was copied or translated. However, this relationship can be so varied and complex that it is not possible to identify it other than through the two texts that establish it. Similarly, the way in which a printed edition was produced cannot be better characterized than by considering the pair it forms with the text from which it was produced. The invention of printing does not change this fact.

But if the existence of such a relation is indeed necessary for any manuscript or print, the identification of the text from which it was made is fundamentally uncertain. How can we determine the text used by Commandino for his edition? How can we even know whether he used a manuscript or a printed edition (see Vitrac (…), Vitrac & Herreman forthcoming)? Having only Commandino’s edition, how can we determine the nature of its relationship to its source? This relationship, given by the pair of the two texts, the uncertainty concerning one affects the other, and the a priori indeterminacy of their relation does not allow for the identification of the model. Both the purpose of the link representing this relationship and the relationship represented are therefore uncertain. The combined uncertainties of the model and the relation of a manuscript or printed edition to it entail a double indeterminacy constitutive of the problem of identifying a model.

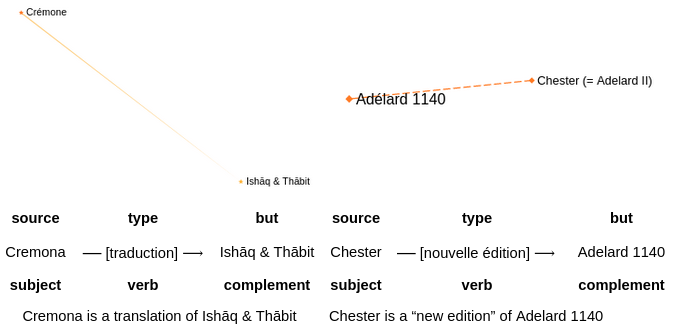

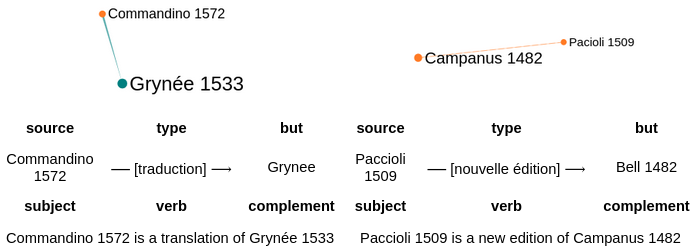

To mark the distinction between cases where the two texts are in different languages or not, we will use the type “translation” in the former case and “new edition” in the latter. These two types encompass all possible relationships between a text and its source, and it is often just as difficult to determine that a text is the result of a translation as it is to identify the model. The issue of double indeterminacy arises equally. Determining whether Commandino’s edition is simply a translation presents no problems of a different nature than determining its model.

It is also important to distinguish the significant case of lost manuscripts ( Greek,

Greek,  Latin,

Latin,  Arabic, etc.). The characteristic form of the nodes associated with them allows for their identification on the graph. The links for which they serve as the source or destination have the particularity that they obviously cannot have been established based on their attested textual characteristics. Between the lost autograph of an edition (e.g., Théon), a translation (e.g., Adélard 1140), or a recension (at-Tûsî 1248), and one or more preserved copies (◾), the link ‘new edition’ here simply means that the second is a preserved representative of the first. The significance is less determined and indicates a dependency or relationship when both manuscripts are lost; this dependency or relationship, which cannot have been established through textual comparison, is inferred from testimonies or results from analyses produced in the case of critical editions. For example, the preface of the Leiden codex informs us that the Arabic translator al-Hajjâj revised his first version to produce a second version that was revised and devoid of any superfluities; if we give it some credibility, it justifies a link (also called ‘new edition’) between the two Hajjajian editions. An example of the second situation: the critical edition of the Campanus 1259 recension by Busard provides a list of sources used by Novarais, including the versions of Adélard 1140, (Robert de) Chester, (John of) Tynemouth, etc. Hence, the ‘new edition’ links are used to denote these dependencies of varying extension and intensity.

Arabic, etc.). The characteristic form of the nodes associated with them allows for their identification on the graph. The links for which they serve as the source or destination have the particularity that they obviously cannot have been established based on their attested textual characteristics. Between the lost autograph of an edition (e.g., Théon), a translation (e.g., Adélard 1140), or a recension (at-Tûsî 1248), and one or more preserved copies (◾), the link ‘new edition’ here simply means that the second is a preserved representative of the first. The significance is less determined and indicates a dependency or relationship when both manuscripts are lost; this dependency or relationship, which cannot have been established through textual comparison, is inferred from testimonies or results from analyses produced in the case of critical editions. For example, the preface of the Leiden codex informs us that the Arabic translator al-Hajjâj revised his first version to produce a second version that was revised and devoid of any superfluities; if we give it some credibility, it justifies a link (also called ‘new edition’) between the two Hajjajian editions. An example of the second situation: the critical edition of the Campanus 1259 recension by Busard provides a list of sources used by Novarais, including the versions of Adélard 1140, (Robert de) Chester, (John of) Tynemouth, etc. Hence, the ‘new edition’ links are used to denote these dependencies of varying extension and intensity.

Links sourced from a lost manuscript (all languages)

The graph reveals in this regard a significant difference in the treatment of Greek manuscripts compared to others (Latin, Arabic, etc.): numerous links between preserved Greek manuscripts are indicated; this is not the case for manuscripts preserved in other languages; the determined links always involve a lost manuscript for those languages. The corresponding relations do not proceed from an identification established by the comparison of manuscripts to which it refers. It is, of course, a difference of historical and historiographical nature: either there are no preserved witnesses of a historically attested version (Hajjajian versions), or there is no critical edition yet (so-called Ishâq-Thâbit version), or such editions exist but have not led to a classification of manuscripts (Arabo-Latin translations and recensions).

Links of the ‘copy’ type between manuscripts (all languages)

Manuscripts are, for the most part, the work of copyist-calligraphers whose fundamental motivation is the reproduction of the text, if possible without alteration, unlike (rare) editors, revisers, and scholarly copyists who aim to improve it. Therefore, these copies have hardly undergone any other transformations than those associated with this mode of transmission (errors, mutilations, misinterpretations of certain marginal annotations, for example, confusing a scholium with a correction or a textual variant).

This is a major difference with printed editions, free from the conservation issue and mostly the product of their ‘interpreter,’ implying editorial intervention, their relationship to their ‘model’ being fundamentally different from that of a copy to its model. For manuscripts, there is an elementary relationship defining a specific type of link: the copy. This elementary relationship has no equivalent for printed editions. However, the problem of double indeterminacy remains, but in a specific form. Indeed, while the copy defines a determined relationship between a manuscript and its copy, their differences are equally indeterminate. A priori, it is not possible to determine the model from its copy, just as it is impossible, for the same reason, to characterize the copying mode from the copy alone.

This indeterminacy combines with another independent phenomenon: the loss of manuscripts. The oldest surviving complete copy, the Vaticanus græcus 190, copied around 830, is roughly equidistant between Euclid’s autograph — presumably written around 300 BCE — and us; thus, we have very fragmentary access to the first eleven centuries of text transmission. The variations in the density of nodes also suggest that many Greek copies prior to the Palaeologan phase have disappeared: before 1260, in all categories combined, 12 copies are preserved; after 1250, 116. None of the 12 ancient witnesses is a copy of another; their models are therefore inaccessible to us.

The opposite case for printed editions corresponds not so much to the improbable case of an edition in which all copies have been lost but to the case of an edition whose existence is unknown. A manuscript can always be considered either a poor copy of a given manuscript or a perfect copy of a lost manuscript. The uncertainty about the model, induced by its possible or even probable loss, and the uncertainty of the differences between the copy and its model, thus once again lead to a double indeterminacy that is also constitutive of the problem of identifying a manuscript’s model.

This double indeterminacy poses a common problem for identifying the models of manuscripts and printed editions, but with foundations and characteristics specific to each, giving rise to specific problems.

Thus, the phenomenon of copying and the consideration of manuscript loss lead to distinguishing a relationship of kinship between two witnesses of the text, i.e., the relationship between a manuscript and another that is not its direct copy, either because intermediate manuscripts of an undetermined number are lost or because this indirect link should not be understood as a chain of copies (which would constitute a first determination) but as a specific form of relationship between a model and its copies, a relationship that we will call ‘derivation relationship’.

Without a clear limit being established, the elementary relation of copying indeed allows us to distinguish, for a given set of models, the manuscripts considered to be direct copies (‘copie’) from those considered to be descendants (‘parenté’). Despite the possibility of unknown printed editions, the absence of any elementary relationship between them does not allow for a similar opposition. Furthermore, since this opposition relates to the relationships between preserved manuscripts, MÉδÉE will also not apply it to manuscripts in languages other than Greek.

Links of type ‘parenté’ between manuscripts (all languages)

But if the phenomenon of copying leads to a distinction between manuscripts and printed editions, and if, for completely different reasons, the opposition between copying and descent distinguishes Greek manuscripts from all others, these distinctions no longer hold for translations, whether they are manuscript or printed. The relationship to the model, which is irreducible to the copying phenomenon, makes their authors a particular kind of editor. It offers great possibilities for variation, especially in formulations, style, and vocabulary. However, these variations are not of the same nature as the liberties taken by recension editors. The fact that some of the first translators had to forge a geometric vocabulary in the language of translation is related to the fact that they reasonably respect the structure of the model. This fidelity sometimes extends even to the letter of the text in cases of word-for-word translation, as in the case of the anonymous Greek-Latin translation transmitted in Par. lat. 7373. But methods will improve, and some translators are true editors, occasionally comparing multiple models.

This justifies a common treatment of the relationships between manuscripts and printed editions, with or without a change of language (except for Greek manuscripts).

The significance of the links

Varied and complex relationships

The significance of the links can vary depending on the parts of the graph. This is due to at least two distinct reasons: the history of these relationships and the analyses that have been made. In this part, we focus on Greek manuscripts and printed editions from the period on which our analyses have focused. The relationships between these versions are very diverse and can be highly complex.

Each manuscript or printed edition has a relationship specific to its sources, which would justify giving it its own representation. The difficulty lies in reconciling the desire to provide a representation that is necessarily quite uniform with respecting its diversity and complexity. The links in the graph provide a uniform representation. The associated publications, and especially the editions to which the graph provides access, allow for an understanding of their diversity and complexity. The notices attached to the links attempt to specify the variously developed analyses that underlie them.

The complexity of the relationships between certain versions requires elaborate analyses. The analyses developed for this purpose, while not always able to fully capture this complexity, cannot be uniformly applied to all the texts in the entire corpus. Once again, the notices are there to indicate in each case what it is.

Notice on a link

The purposes of the links

Introduction

To account for the significance of the links shown on the graph, it is necessary in all cases to first distinguish between the source and the target. With the exception of Euclid’s autograph, which is not shown on the graph…, all its descendants must have been made from at least one previous version. Thus, each node in the graph must necessarily be the source of a link. For each node, a (piece of) link can therefore be immediately represented with this node as the source.

Then it remains to account for the significance on the graph of:

purpose of the link;

type of link;

support of the link.

The determination as well as the significance of the purpose, type, and support of the link are closely interdependent. The determination of its type depends on its purpose, and the determination of its support depends on both its type and purpose, all depending on the source. However, we will treat them as distinct as possible in order to indicate their respective specificities.

The target as representation: the principle of representation by the oldest node (p.r.o.)

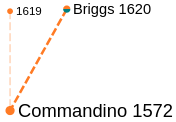

Let’s take the simple example of the link between the node ‘Briggs 1620’ and ‘Commandino 1572’. This link indicates a relationship between the Latin text in Briggs’ 1620 bilingual edition and Commandino’s 1572 translation. However, there is a reedition of Commandino’s edition in 1619. We do not know if Briggs used one or the other. From this point of view, both editions are indiscernible. Each could be the purpose of a link from the ‘Briggs 1620’ node. The choice of one over the other is essentially arbitrary. It is important to make a choice and ensure that this choice is as uniform as possible across the entire graph. We have decided to choose the first node for which the represented relationship is valid, that is, the oldest one shown on the graph. This is the principle of choosing the oldest representative (p.r.o.).

For printed editions, choosing the closest edition in time and location to the edition at the source of the link would have been inextricable. The first edition is generally well-known, and digital versions are often available.

The node at the target of a link is a node that represents all the nodes for which the represented relationship is equally valid. It is simply the oldest one shown on the graph. Even though they have a unique purpose, the links identify sets of nodes, namely all the nodes in the graph located above their purpose that can satisfy the relationship represented by the link.

However, the relationships must have an empirical textual basis; they refer to documents. For manuscript nodes, it is the corresponding manuscript when it has been preserved. For printed editions, it is the copy that serves as the representative of the node. Therefore, the node at the target, like the node at the source, also indicates the document that serves as the empirical basis for the relationship represented by the link, except for those representing lost manuscripts.

Conversely, the other links from the target node, considered with their type, provide an indication of the nodes to which the link is likely to extend.

In the present case, there is also an Italian translation from 1575, from the Commandino edition, with a re-edition in 1619 as well. The graph shows links that all have the edition of Commandino from 1572 as their target based on the principle of representation by the oldest node (r.n.p.a.). Each person can then appreciate the relevance of the possibility of relating them to other nodes. For example, the Latin re-edition from 1619 having the Italian translation from 1675 as its source or even the 1619 re-edition.

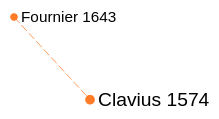

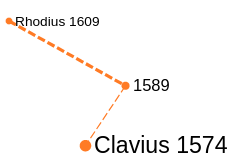

For example, the edition of Clavius 1574 is also the target of the link from the source ‘Fournier 1643’ because we have found nothing that would justify establishing a link with a later edition of Clavius. On the other hand, the edition of Clavius 1589 is indicated as the target of the link with the edition of Rhodius 1609 because they have more common aspects than with the edition of 1574. Similarly, the link was placed on the edition of 1589 because we have found nothing that would justify establishing a link with the editions of Clavius from 1591 or 1603.

The nodes are representatives in three different senses that should be distinguished:

as a node: they are the representatives of the texts they are associated with;

as the target of a link: they are the representatives of the nodes to which the relationship represented by the link is also valid;

as the source of a link: they are the representatives of the texts represented by the node but reduced to the support of the considered link.

Links related to the corpus

However, the r.n.p.a principle also implies that the same relationship is not verified for any of the nodes in the graph that are older than the one chosen. Apart from obvious chronological considerations (a text does not use a later version…), determining the target of a link involves all the nodes in the graph, ultimately the complete corpus of Euclid’s manuscripts and printed works. The link between Briggs 1620 and the edition of Commandino from 1572 indicates that the dependency it represents is stronger with the edition of Commandino from 1572 than with all other nodes, except for those for which the principle of the oldest representative applies. Therefore, the value of the links depends on the corpus in which they are found. The extension of the corpus inversely affects the extent of the verifications necessary for establishing a link.

A version can only have a link with another version that is present in the graph, so it is important for the graph to be as complete as possible from this point of view. Thus, in a corpus that is reduced to two texts, any other text can only be modeled after one or the other, which can be easily and rigorously established. However, the conclusion obtained will still depend on the very limited corpus considered. Regardless of the similarities between two versions, establishing a link between them involves the entire text corpus.

While some possibilities can be excluded for more or less valid reasons, such as the French edition of Forcadel from 1564 being the translation ofa lost Arabic manuscript, the remaining possibilities, both for the manuscripts and the printed editions, require considerable verifications. Again, these verifications are necessary when one does not rely solely on the indications given by the authors.

The two dimensions of links

The extent of verifications required for establishing a link includes two dimensions, one according to the extent of the text considered (first dimension), and the other based on the extent of the corpus considered (second dimension). The first dimension, the extent of the considered text, defines the support of the link.

Keywords and links

Keywords have the advantage of defining very well-defined relationships, namely those that can be deduced from the definition of the keyword.

The extended keywords (see above) do not define any relevant extended support links. For example, the keyword related to the existence of “Euclidean” proofs would lead to creating links of a relatively well-defined type, with the entire text as the support but with any version containing that keyword as the source, and the oldest among them as the target on the graph.

Punctual keywords (see :ref:above <punctual_keywords>)can create very well-defined links with punctual support,which are too restricted to establish truly relevant links between two versions. Combinations of keywords are much more relevant for this purpose, and the graph’s functionalities allow visualizing all possible logical combinations of keywords. This visualization is useful, but the established link support remains limited to the number of considered keywords, resulting in scattered points throughout the entire text. This is far too little to establish meaningful dependency relationships between two texts.

However, certain combinations can be sufficient to characterize graph links. They are significant insofar as they involve the entire corpus (second dimension). However, they should not be confused with the relationship represented by the link, as they cannot account for its type or extension, i.e., its support, except for defining the type through these few keywords and reducing the support to a few points.

The graph features allow finding common keywords between any two nodes, and when a sufficient number of keywords is retained, these common keywords establish a well-defined, textually based relation that often only holds true for these two nodes. Thus, one could justify a link between almost any nodes. Keyword combinations, therefore, only control the represented links, not establish them.

This also shows that with types of links defined too flexibly, which can vary with each pair of considered nodes as allowed by the various combinations of keywords, almost any node could be the source of another. It is, therefore, necessary to have few types of links and ensure their definition is consistent throughout the corpus.

Link types

The preceding discussion has established the necessity of having a reduced number of uniformly defined link types throughout the corpus (second dimension). The limited number of considered types (‘copy’, ‘parentage’, ‘translation’, ‘new edition’), with the first two specific to manuscripts, satisfies this condition and guards against the pitfall of an overly flexible typology that would only register the biases used in its definition.

The link types ‘copy’ and ‘parentage’ are specific to manuscripts. They describe the relationship between two copies based on the comparison of their shared divergences, codicological and philological. These divergences have been identified in a sample of the text (approximately 20%).

The suggested dependence between two copies can be strong (‘copy’) or less strong (‘parentage’). The ‘copy’ relationship also implies the chronological priority of the model over the copy, while ‘parentage’ does not presuppose such a priority and can apply to undated manuscripts that are chronologically close.

Any information about their models given in the texts is additional to the independently established relationships.

The notices on the links serve to specify these different cases and provide specific clarifications.

In the case of printed works, particularly for the period analyzed in our study, the link types ‘new edition’ and ‘translation’ cover dependencies that can vary greatly in nature and complexity. They do not have an intrinsic definition of their own. They simply retain the relevant opposition of maximal extension always applicable to two editions: whether they are of the same language or not.

Link supports

None of the four types considered has a determined a priori support. Their support can be the entire text or any part of it, whether connected or not. For prints, these supports are generally too complex to be simply described. In manuscripts, this is not the case: they are intervals in most cases, reflecting the use of several successive sources, which is manifested by the existence of several links leading to the same node.

For manuscripts, any aspect of any textual unit can be used in the establishment of a link, including material characteristics (such as layout, codex composition, annotation, deterioration, or restoration of the copy) as well as textual characteristics. In contrast, for prints, the considered textual units are limited to those of the main text, i.e., the principles (definitions, requests, common notions) and the statements and proofs of propositions. A priori, excluded are proofs aliter, comments or scholia, and various additions. However, there are exceptions for certain proofs aliter transformed into proofs, particularly important scholia (scholium at the beginning of Book V), and relevant additions for establishing filiations.

The support of links between manuscripts (such as ‘copy’ or ‘parentage’) is determined in terms of constituents, either material (such as the quires composing the manuscripts) or textual (the Books or groups of Books) for which the relation is valid.

Several codicological phenomena specific to the transmission of a long text like the Elements (copying by juxtaposition of successive models; restoration of deteriorated portions) result in several links that can converge at the same node.

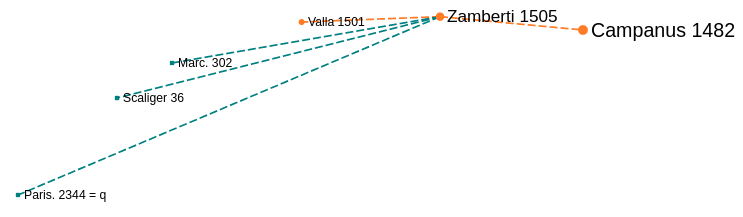

For example, the support of the link between Zamberti and the Paris. 2344 consists of portions I.Df—VIII.25 (partially) + Books X-XI. The change of model was necessary due to the loss of a quire that caused the disappearance of the portion VIII.25 (2nd part)—IX.14 (1st part). However, for the end of VIII.25 and the portion VIII.26-IX.36, Zamberti chose another manuscript, the Marc. gr. Z 302, even though he was not obliged to do so for IX.14 (2nd part)-IX.36: it is an editorial choice. For Books XII to XV, a third copy was used, the Leidensis Scaliger gr. 36; see diagram above. It should be noted that the identification of the models of the printed version of 1505 was greatly facilitated by the fact that they are the same models that the Venetian had used to copy the Leidensis BPG 7; in this case, the screen that the phenomenon of translation from Greek to Latin can create does not exist.

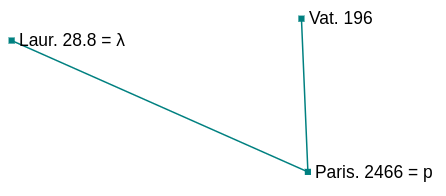

The differences in the supports of links, potentially combined with an economy principle, make the use of the r.p.a. principle rather rare for manuscripts. Let’s take the example of the link between the node ‘Vat. 196’ and ‘Paris. 2466 = p’:

This link indicates a copying relationship between the manuscript Vat. 196 and Paris. 2466 = p. However, it would also be conceivable that Vat. 196 was copied from Laur. 28.8 = λ, rather than from the older Paris. 2466 because the same link also exists between Laur. 28.8 = λ and Paris. 2466, and these two manuscripts are indiscernible in this regard: a link could also be placed between λ and Vat. 196. But the support of the link between Vat. 196 and Paris. 2466 is the portion VIII.21 (partially)—XIII.18, while the support between λ and Paris. 2466 is the portion XI.34 (partially)—XIII.18. Therefore, if we were to posit a hypothetical link between λ and Vat. 196 based on the support XI.34 (partially)—XIII.18, we would also have to consider a link between Vat. 196 and Paris. 2466 for VIII.21 (partially)—XI.34 (partially). The economy principle dictates choosing a single link, the one with the largest support.

XI.34 (partially)—XIII.18, however, we should also consider a link between Vat. 196 and Paris. 2466 for VIII.21 (partially)—XI.34 (partially). The principle of economy dictates choosing a single link, the one with the largest support.

The notice attached to a link specifies its support, i.e., the extent of the considered relation (related Books or quires, gaps, etc.).

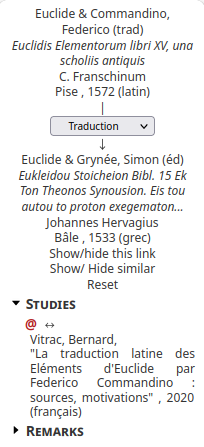

Secondary literature on links

As with nodes, MÉδÉE provides a selection of works specifically dealing with relations between manuscripts and prints. These works are also distinguished based on whether they include:

a study of the considered link

only remarks

critiques

or only cite it

Publications by type related to a link

The listed publications are related to the specific type of link (“copy,” “parentage,” “translation,” etc.) indicated in the dropdown menu at the top of the left panel.

As with nodes, it is possible to observe the recurrence of certain assertions related to links between versions, regardless of their validity. However, these cases are more numerous than they appear in the graph because we did not include links that we consider not to exist. However, these references are found among those making remarks about the two nodes involved.

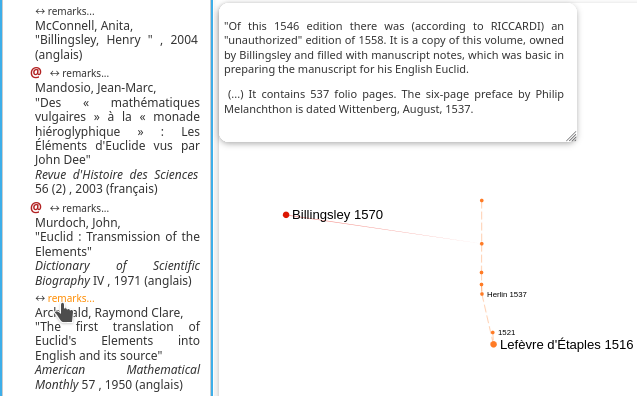

For example, the analysis of Billingsley’s edition only allowed for the establishment of a link with Lefèvre d’Étaples 1516 without being able to distinguish whether it refers to this edition or one of its reprints. But annotations by Billingsley himself on a copy of the 1558 reprint reported in Archibald 1950 suggest that it is specifically the 1558 edition that was used. Therefore, this edition is indicated as the target of the link. Archibald’s article is listed among publications making remarks about this link. These remarks, which account for the choice of the target, can be viewed by clicking on the ‘remarks…’ entry associated with this publication. This information is thus not disassociated from the publication that originated it. However, it only complements the analysis of the relationship between Billingsley’s edition and Lefèvre d’Étaples 1516, without replacing it.

Quotation of remarks made by a publication about a link