MÉδÉE

Manuscripts and Editions

ofEuclid's Elements

Typology of Dependencies

Bernard Vitrac & Alain Herreman

To report any correction, suggestion, or request, please contact: alain.herreman@univ-rennes.fr

A well-defined, effective, complete, and minimal vocabulary is proposed for describing the main characteristics of both dependency and independence relations between texts, applicable to statements, proofs, and figures. Based on this vocabulary, a typology of editions, including translations, can be established according to their relationship with their sources. This vocabulary and typology allow for expressing all the results obtained during the analyses performed with the corpusanalysis program, thereby contributing to the control of its conclusions.

The proposed definitions must be:

well-defined;

effective: the performed analyses allow determining whether each definition applies or not;

complete: they express all the results obtained from the performed analyses.

minimal;

Mutual definitions are given by complementarity.

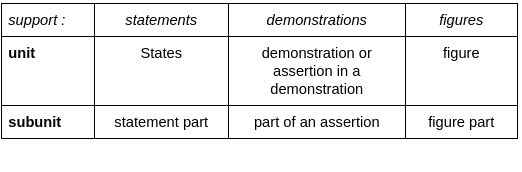

Elementary Dependency Supports

Typology of elementary supports on which a dependency relies.

Examples

The support of almost all aspects is a subunit.

Aspects related to the “structure” of the text generally refer to units. For example, the position, existence, or absence of a statement.

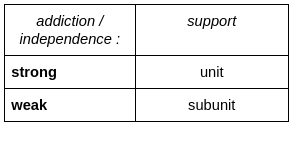

Elementary Dependencies and Independences

Typology of elementary dependencies.

Absolute Definitions

A strong dependency (resp. independence) is a similarity (resp. difference) between two texts on a unit that establishes their dependency (resp. independence).

A weak dependency (resp. independence) is a similarity (resp. difference) between two editions on a subunit.

Note: Most registered aspects determine weak dependencies or independences. Only direct comparison allows establishing a strong dependency.

Examples

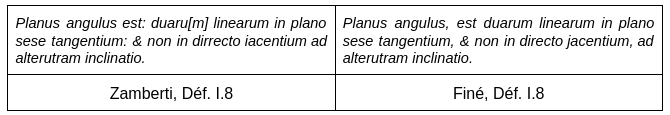

Strong dependency from Fine to Zamberti on Definition I.8: Fine’s formulation of Definition I.8 is a literal repetition of Zamberti’s

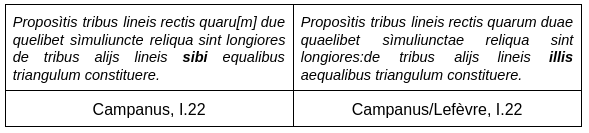

Strong dependency from Campanus/Lefèvre to Campanus on I.22: Campanus/Lefèvre’s formulation is a literal repetition of Campanus’s except for “sibi” replaced by “illis”. The difference between “sibi” and “illis” is a weak independence.

Strong dependency from Henrion to Dounot on proposition IX.12.

Strong dependency from Le Mardelé to Clavius on the proof of III.7.

The same articulation between two statements determines a weak dependency.

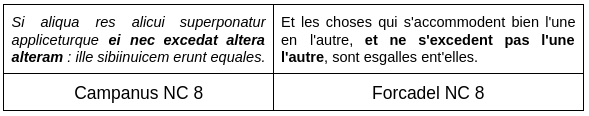

Weak dependency from Forcadel to Campanus on part of NC 8: Forcadel’s formulation of NC 8 includes an aspect taken from Campanus without reproducing the entire formulation

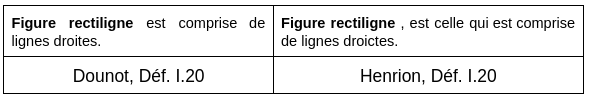

Weak dependency from Henrion to Dounot on Definition I.20, which he states in the singular, an innovation by Dounot, without reproducing the rest of its formulation literally.

Weak dependency from Henrion to Dounot on I.26, where he reproduces the occurrence of “sçavoir” in the same place.

Weak dependency from Henrion to a Latin edition due to the use of “quand” at the beginning of I.13 (attested by Henrion at the beginning of no other proposition in Book I).

Strong independence from Le Mardelé to the Clavius edition on the proof of III.7.

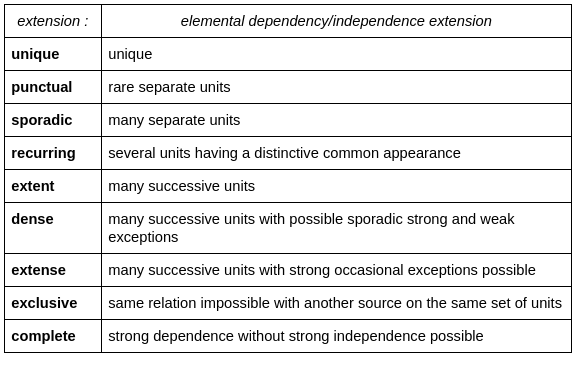

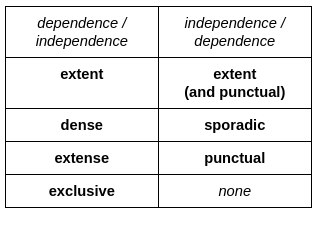

Extensions of elementary dependencies and independencies

Complementarities of different extensions

For example

A dense dependency allows sporadic independence.

An extensive independence allows punctual dependency.

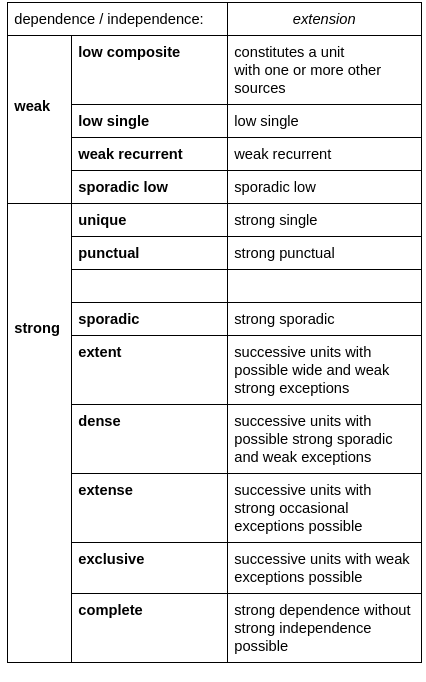

Dependencies and independencies from a source

Typology of possible dependencies and independencies from an edition to a source.”

NB: For extended, dense, or exclusive dependencies, “strong” can be implied.

Examples

Recurrent weak dependency from Fine to Campanus on Book I: use of “punctum”, used by Campanus, instead of “signum” used by Zamberti.

Recurrent weak dependency from Fine to Campanus on Book I: use of “punctum”, used by Campanus, instead of “signum” used by Zamberti.”

Sporadic weak dependency from Le Mardelé to Henrion

Unique strong dependency from the Errard edition to the Candalle edition on the Common Notions: out of the 12 Common Notions, Errard only takes NC 8 from Candalle.

(Strong) sporadic dependency from Errard to Candalle (resp. Forcadel) on definitions

(Strong) extensive dependency from Errard to Candalle (resp. Forcadel) on propositions

(Strong) dense dependency from Errard to Forcadel on the Common Notions.

Extensive independence from Clavius to Commandino on the proofs of Book X.

Punctual strong independence from Le Mardelé to Clavius on definitions: Le Mardelé provides the definition of a circular segment in Book I, unlike Clavius.

Strong independence from the Errard edition to Grynée on the proofs of I.2 and I.7

Punctual strong independencies from Commandino to Grynée, where Commandino does not follow the structure of the principles in Book I, adds propositions in Book V, and reverses the order of propositions X.10-11.

Exclusive dependency from Fine to Zamberti on the definitions of Book I: Fine literally adopts Zamberti’s definitions without strong exceptions (using “punctum” instead of “signum”, no use of “sous” in two definitions).

Weak dependency from Dounot to Errard: Dounot formulates I.45 relative to a “rectilinear figure,” which is an innovation by Errard.

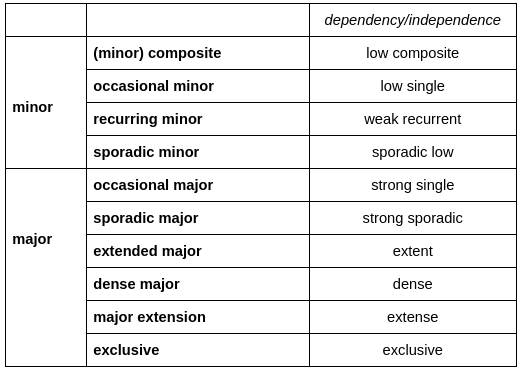

Dependencies and independencies from a source to an edition

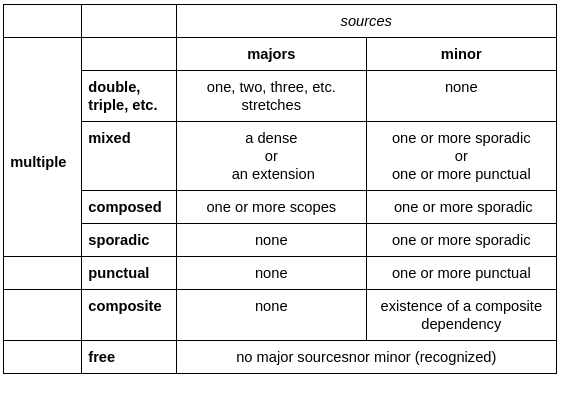

Typology of sources in relation to an edition:

Note: “major” can be implied.

Examples

Henrion is a sporadic minor source for Le Mardelé.

Candalle is a (major) punctual source for Errard on the Common Notions.

Campanus (resp. Zamberti, resp. Magnien-lat) is a sporadic (major) source for Forcadel.

Candalle (resp. Forcadel) is an extended (major) source for Errard on the propositions.

“Dounot is a dense source for Henrion on the propositions of Book I.

Zamberti is an exclusive source for Fine-lat on the statements of Book I.

Magnien is an exclusive source for Forcadel on the figures of Book I.

Magnien-lat is an exclusive source for Clavius on the statements of Book I.

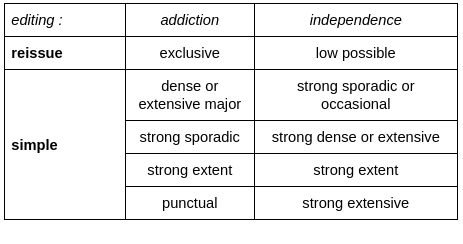

Editions

Typology of editions in relation to their sources

Single-source editions

Examples

Forcadel’s edition is a reedition of Magnien on the figures in Book I

Candalle’s edition is simple, with Zamberti’s edition as the only major source (dense).

Forcadel’s edition is simple on the common notions.

Multiple-source editions

Note: In all cases, minor sources are possible.

Examples

Zamorano’s translation is a reedition of Zamberti.

Commandino’s translation is a* simple translation* of Grynaeus (with strong sporadic independencies).

Clavius’ edition is a dual edition for his statements with sources Magnien and Commandino (Book X).

“Errard’s edition is a dual edition on the propositions of Book I, with extended sources being Forcadel’s and Candalle’s editions.

Henrion’s edition is a dual edition on the statements and demonstrations of Book I, with (major) sources being Dounot’s and Clavius’ editions.

Le Mardelé’s edition is a mixed edition with Clavius’ edition as the major source and Henrion’s translation as the minor source.

Forcadel’s edition is composed, with Zamberti’s edition as the extended source and sporadic sources being Campanus and Magnien.

Forcadel’s edition is a sporadic edition on the definitions, with major sources being Campanus, Zamberti, and Magnien (none of them being a principal source (dense) on the definitions)

Errard’s edition is composite, as I.32 is the result of a combination of aspects from Forcadel’s edition and aspects from Candalle’s edition.

Forcadel’s (resp. Candalle’s) edition is a composite source for Errard’s edition (I.32).

Fine’s edition is a free edition for the demonstrations

Dounot’s edition is a free edition for the demonstrations.

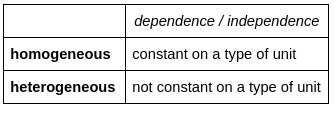

Homogeneity and heterogeneity

Finé’s edition is homogeneous on the statements and demonstrations of Book I (although the sources are different)

Forcadel’s edition is homogeneous on the figures of Book I.”

Henrion’s edition is heterogeneous on the statements and demonstrations of Book I.

“Clavius’ edition is homogeneous on the statements and demonstrations of Book I (although the sources are different).

Le Mardelé’s edition is heterogeneous on the demonstrations of Book I.

Commandino’s edition is homogeneous on the statements and demonstrations of Book I.